The Cost of Nonprofit Accounting

Article published by Raffi Yousefian, Principal at RY CPAs on 07/07/2021

How much does nonprofit accounting cost? How much should you be paying? The short answer is, it’s expensive and it depends. In this article, I will explain the dependencies that significantly influence the cost of accounting for nonprofits.

Before we dive in, let’s understand the purpose of nonprofit accounting and the options that are out there. The purpose of nonprofit accounting is to:

- provide beneficiaries, management, the board, funders, and other stakeholders with an accurate representation of the organization’s performance and financial position;

- stay compliant by filing timely information returns and relevant taxes;

- avoid theft and catch errors; and

- ensure vendors and employees are paid (if applicable) and payments are received

As outlined in our 4 Reasons to Outsource Your Accounting Function article, there are a couple of options for achieving this:

- hire a bookkeeper throughout the year plus an independent CPA at the end of the year to prepare the 990 and the audit

- hire an outsourced accounting firm to do the accounting throughout the year and prepare the 990 at the end of the year, then hire a separate independent CPA to prepare the audit at the end of the year

- hire a controller, finance director, or CFO in-house

In this article, we will focus on the first two options. The option you select will affect the pricing, but it shouldn’t change the ideal price. To understand what you need to pay, you will need to understand the cost drivers for accountants so you’re not confused about the wide range of pricing when considering your options.

Why is nonprofit accounting expensive?

Most nonprofits require three-dimensional reporting. Two-dimensional reporting is recording and presenting transactions by date and account. Three-dimensional reporting adds a class or location which allows you to track the expense’s function, program, and/or fund for each transaction. The addition of this third dimension makes things drastically more complicated because some transactions can be split and allocated in the third dimension. For example, employees’ salaries in a two-dimensional accounting system will be recorded as salaries expense on a certain date. In a three-dimensional accounting system, you must also capture the functional expense and categories in which the salaries are to be recorded. This requires the accountant to allocate the salaries expense based on a variety of factors across various functions including fundraising, administrative, program 1, program 2, etc. This can get very complicated and time-consuming and is mostly unique to nonprofit accounting.

Volume & Scope

The cost for nonprofit accounting is typically driven by volume. A nonprofit grossing $1m in revenue should theoretically have fewer bills, employees, and bank/credit card transactions than a nonprofit grossing $5m in revenue, so higher revenue increases the amount of work for the accountant and therefore the cost. However, volume and revenue also affect the scope of work. A nonprofit with $5m+ in revenue should delegate more to an accountant than a nonprofit with $1m in revenue. One service that might be managed in house by a $1M nonprofits but delegated by a $5M nonprofit is bill pay and processing, because the management of the larger organization will not have time to prepare, approve, and issue bill payments accurately and timely, while also running the organization and maintaining the appropriate segregation of duties.

Revenue Sources

After volume, the second most impactful driver of accounting costs in a nonprofit is the sources of revenue. If your revenue is comprised of mostly smaller contributions without donor restrictions from the public, then accounting for the revenue in your organization should be fairly straightforward. On the other hand, if your revenue is solely or mostly comprised of larger contributions with donor restrictions from contracts or grants, then the accounting for these sources of revenue is increasingly more complicated because the organizations will need to track revenue and expenses separately for each restricted revenue source. This may seem clear-cut, but keep in mind that most nonprofits require three-dimensional reporting as noted previously.

An experienced nonprofit accountant should be able to understand exactly how much work is required to provide accurate and informative three-dimensional reporting as measured by your revenue amount and sources. Your accountant should ask more questions and look at your existing books to understand if there any nuances beyond the revenue sources and amounts that could affect the price. Here are the most frequently observed nuances that could affect the cost of accounting:

- Whether you use a system like Little Green Light to automate recording donations

- Number of fundraising platforms and organization of revenue records

- Frequency and quality of communication between the fundraising/development team and accounting.

- Reporting for individual funders

- Cost-reimbursement contracts

- Long-term pledges

- Expenditures of Federal Awards

- Adherence to organizational documentation policies

- The onus of financial management controls

Quality & Accuracy

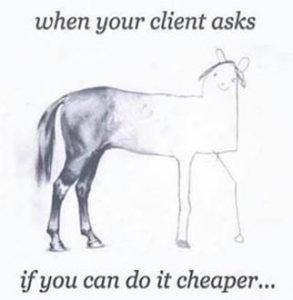

Gauging the quality and accuracy of your nonprofit’s financials is difficult when you’re not an accountant, but it’s very important because it is the third-most impactful driver of price in nonprofit accounting after volume and revenue sources. Many accountants provide value-based pricing, which basically translates to “pay us whatever you can and we will adjust our services to cater to your budget.” Two different accountants can provide you identical lists of services they will provide, yet the results for those services could be completely different. Let’s look at a couple of services and how they can differ between accountants.

Here’s a service item from one of our monthly plans: Record And Reconcile Invoices/Pledges and Deposits. There are many corners that an accountant can cut to provide effectively this same service item for half the price so they still stay profitable. For example, they could recognize revenue based on pledge or invoice date instead of recognizing revenue in accordance with the terms of the grant agreement. Another example of cutting corners related to this service item is recording deposits on a cash basis instead of accurately reporting them as payments on pledges or invoices.

Here’s an example of a more common service item offered by accountants: Reconcile Bank And Credit Card Transactions. This could mean a thousand different things, and many accountants like that because it gives them flexibility in delivering scope (aka the ability to cut corners). Some of the tactics an accountant can use to cut corners for this service item are:

- Running credit card donations through a clearing account instead of reconciling the deposits with the revenue recognition

- Recording transactions on a cash basis instead of on the accrual basis or a hybrid rather than the full-accrual basis

- Not attaching documentation to the transactions in the accounting ledger

- And the list goes on….

Another service item that an accountant could easily cut corners on is accounts payable including the Bill Pay and Vendor Reconciliation. Let’s look at two scenarios when delivering this service:

Accountant 1:

- Receives a legal bill dated March 20 on March 22, for a retainer on attorney services to be used in May

- Records the bill in QBO dated March 20 and classifies it as legal expenses with functional expense class of 50% G&A and 50% Programs.

- Pays the bill, then records the payment in the accounting system, and matches the payment with the bills.

Accountant 2:

- Receives a legal bill dated March 20 on March 22, for a deposit on attorney services to be used in May

- Records the bill in QBO dated March 20 and classifies it as Prepaid Expenses.

- Later records a journal entry to recognize the legal expense in the month that the expense is actually incurred/applied to legal bills by the attorney, and allocates the expense based on the allocation plan.

- Requests a W-9 from the vendor if one is not already on file.

- Submits the bill payment for client approval through Bill.com only after receiving a W-9 from the vendor

- After the bill payment is approved, the accountant pays the bill, then records the payment in the accounting system, and applies the payment toward the bill.

Which accountant provides a larger net benefit to donors and to the overall internal controls of the organization? Guess which accountant charges more? Clearly, the answer to both questions is Accountant 2; however, for micro-sized organizations, all of this should probably be done internally or by a voluntary board member because the cost will outweigh the benefits.

Here is a more general list of questions you can ask when presented with a “too good to be true” price:

- Will the books be prepared on a full accrual basis or cash basis? Or a hybrid? If a hybrid, then which component will be cash basis and why?

- What is your process for recording and recognizing revenue?

- How will credit card donations and donations from other third-party systems be recorded and reconciled?

- How will the payroll be recorded?

- Will you do end-of-month payroll accruals, if payroll is on a biweekly schedule?

- If handling accounts payable, will you simply be paying whatever you are presented with or will you follow a due diligence and expense recognition process?

- How frequently are the books reconciled? Weekly or monthly?

To sum it up, if two accountants are more or less equal in competence and experience, and one is charging drastically less, then there is a high chance that they are cutting corners. The question to ask yourself is whether the price reduction is worth cutting corners? The answer could be yes. It just depends on which corners are being cut for each service item and whether these are important to your organization. If all of your expenses are paid as they are incurred (instead of prepaid or paid after the fact), then maybe paying more for a full accrual basis accounting system is not worth it. But if 80% of your revenue is comprised of multiple grants with donor restrictions, then we strongly recommend you invest in the proper accounting to make sure the revenue for each grant is (1) recognized in the correct period, and (2) the amount of grant fund balances are available and tracked monthly at a minimum.

To understand which “corners are being cut”, you should request a detailed engagement letter and scope of work that outlines every single service item that the accountant will be providing along with a detailed description of how and when they will execute each service item. Do not leave room for interpretation.

While assessing price versus competence, it is important to remember that an incompetent accountant can lead to very bad publicity for your nonprofit organization in multiple ways. First, the board can lose trust in your leadership. Board members are usually very experienced and know how to read the financials of an organization. If they notice something is off, then they will judge your ability to hire the appropriate people in the organization. For instance, a $2m restricted grant with conditions is improperly recognized in the year the pledge was received. A competent Treasurer will raise concerns about this, and it will affect management’s credibility. Second, consider if the organization’s 990, which is shared publicly, is prepared incorrectly. How will funders and beneficiaries judge the management and effectiveness of your organization? Third, what if you are unable to receive an unqualified opinion on your audit because your books are un-auditable?

The Right Fit

With accounting, you typically get what you pay for unless the accountant is simply not a good fit.

First, size matters, so do not let a big firm do a small firm’s job. If you are a small nonprofit grossing $1m in revenue per year, then you should not engage a big-four accounting firm to do your accounting and taxes. There is definitely a sweet spot where paying more has diminishing returns and you are essentially just paying more because you are not a good fit.

Second, the accountant should be a subject-matter expert or specialist in nonprofits. They might be the best accountant in the world and can figure out how to do nonprofit accounting, but guess who’s paying for the time it takes them to learn how to do nonprofit accounting? You! This goes back to the point of diminishing returns-just because you are paying more does not mean you necessarily get a better service because a portion of that premium is being attributed to a learning curve.

We have inherited many nonprofit clients that are in the $500k-$2m revenue range that were previously working with huge national firms and paying extremely high prices but receiving terrible service because they simply were not the right fit. Conversely, if you are a $100m/year nonprofit, then you probably should not work with a firm like ours as we simply would not be able to support you properly.

The sweet spot is finding a competent accountant that specializes in nonprofits that can provide a quality and accurate service at a fair price point.

How much should you pay?

With that said, how much should you pay for nonprofit accounting? The amount you pay should be based on cost/benefit like anything else. Revenue is the best indicator of whether the cost of accounting is worth the benefit. The chart below gives you an idea of the range of costs you should pay at each revenue tier to get the right balance between cost and benefit.

|

Revenue |

Monthly Price |

|

<$500k |

$600-$1500 |

|

$500k – $1,000,000 |

$800-$2000 |

|

$1,000,000-$1,500,000 |

$1000-$2500 |

|

$1,500,000-$2,000,000 |

$1500-$2500 |

|

$2,000,000-$3,000,000 |

$1600-$3000 |

|

$3,000,000-$5,000,000 |

$1700-$3500 |

|

$5,000,000+ |

$1800-$4000 |

Accounting is a service that scales, meaning if you provide the same level of service at $1.5m in revenue and $500k in revenue then the accounting price should not change much. However, the accounting for a nonprofit with $1.5m in revenue should not be receiving the same level of attention as a nonprofit with $500k in revenue. The table takes into consideration the level of services that an accountant should be providing to a nonprofit at each revenue level. For example, at the $1m+ revenue range, a nonprofit should start outsourcing their bill pay to ensure management efficiency and the appropriate internal controls.

The wide range above is due to nonprofits typically having in-house resources that can facilitate some accounting-related tasks, such as submitting and processing payroll. Therefore, you should focus on the minimum and maximum in each revenue range instead. Meaning, if your revenue is between $1.5m and $2m, and you are paying less than $1500 then you should ensure your accountant is not cutting corners. Similarly, if you are paying more than $2500/month then perhaps the accountant is not the right fit.

Conclusion

The amount you pay for accounting and tax services varies depending on a variety of factors, but ultimately a question of how much benefit you receive from the investment and whether that investment is worth the cost to you. We have done that analysis based on revenue for you and presented the results in the table above. If you are in the range of the pricing above; and you are confident in the accuracy of your financials, then you are in the sweet spot for nonprofit accounting costs. Feel free to use this information to help you analyze your current accounting arrangement, and do not hesitate to contact us if you would like our help to get you to the sweet spot!

Leave a comment